Over what was a relatively slow news weekend considering our daily newscycle whiplash, the world turned its attention to the first round of the Brazilian elections, which took place on Sunday (10/07). Even John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight turned his attention to the state of affairs in Brazil, which is both a useful summary and much more entertaining than what you’ll read below.

If you’re still with me and eager to catch-up, here’s a quick round-up of my election-related posts over the past months:

- Latest Polling and Pension Paralyzation in Brazil – September 16, 2018

- Updates on Brazil (and others) – September 9, 2018

- Brazilian election update: Lula ruled ineligible – September 1, 2018

- Brazilian Presidential Elections, August 2018 – A “no win” situation? – August 26, 2018

- Checking in on the Brazilian Elections (May 2018) – May 23, 2018

- Brazilian Corruption and the 2018 Elections – May 7, 2018

- The return of the global caudillo – March 13, 2018

Just to toot my own horn a bit, here’s my take back in March, three months into my time in Brazil:

As familiar as this story [Bolsonaro] sounds, the Brazilian people that I’ve spoken with aren’t yet convinced of the inevitable ascendance of Bolsonaro. As if seeking to validate my hypothesis on the ability of outsiders to evaluate a political temperature, they claim that cooler / more sensible heads will prevail, and that a more palatable, middle-of-the-round candidate (such as former Governor of Sao Paulo Geraldo Alckmin, or former Governor of Ceara Ciro Gomes) will rise above the fray to become the next President of Brazil, as if asking a populace to eat its vegetables, as opposed to the more immediate and attractive short-term “sweets” of Bolsonaro – the law and order, by any means necessary, candidate. To me, this seems like an inevitable outcome and a continuation of the global populist trend.

I’m oftentimes reluctant to offer predictions with any level of certainty, given my conviction in the occurrence of Black Swans and the reality that in fact no one really knows much, but in this case, considering my status as an outsider looking in, I feel like this diagnosis is appropriate. Regardless, an exciting year to come.

While there has certainly been a great deal of twists and turns since March, the economy has remained sluggish, with extremely high rates of unemployment and unabated and alarming crime statistics. Several weeks ago, the Financial Times published a series of helpful charts that contextualized much of the malaise felt by Brazilians leading up to the Presidential elections, entitled In charts: what is bothering the Brazilians?.

While not copying at risk of reproach from FT’s draconian copyright policies, the highlights include:

- An unemployment rate in excess of 12%, the highest in Brazil’s recent history (since 1984)

- A country whose GDP contracted 7% from 2015-16 and continues to slowly recover from its worst recession in history, levels unseen since the pre-Real days of hyperinflation in the 1980s and early 90s (another plug for this enjoyable NYTimes op-ed on the topic)

- Over 64k ‘intentional’ and documented homicides over the past year, a number that exceeds the United States and all of Europe combined (h/t John Oliver for the comparison)

Combine these depressing statistics with Operation Car Wash, and it is easy to see why Brazilians are so disgusted with the state of affairs in the country, leading about 85% of voters to conclude that the country is heading in the wrong direction. The wide-ranging investigation into political corruption implicated most of Brazil’s ruling political class and leading political parties, namely the Workers Party (PT) (home to the now-jailed Lula), the Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB, President Michel Temer’s party) and the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), as well as several of its prized private and private-public sector enterprises, including Odebrecht (construction), Petrobras (oil & gas), and JBS (meat) in graft, bribery, and corruption that totals in the tens of billions.

Amid these circumstances, Bolsonaro’s first round supremacy, where he captured somewhere around 46% of the vote (just short of the 50% threshold for outright victory) is hardly surprising. In a now all-too familiar story, despite Bolsonaro’s lack of access to the typical political organization and traditional campaign tools (including the support of a political party and minimal representation on tv ads), he was able to achieve a massive victory. Using social media (the NYTimes amazingly reported that Bolsonaro spent just $235,000 in support of his campaign, against Haddad / PT’s $6.3M), specifically Facebook and Whataspp, to spread political memes and personal messages directly to the electorate, Bolsonaro was able to build a broad coalition of individuals young and old and across the country (excluding the North East). Like Trump and as a seven-term representative, Bolsonaro was hardly an outsider, but he sold himself as incorruptible and unconnected to the political class, which is technically true, given his limited record of actual Congressional legislative success.

Brazilian voter dissatisfaction did not merely extend to the Presidential elections. Impeached President Dilma Rousseff, who continues to be seen as a martyr by her supporters after being impeached from office in 2016, was romped in a senatorial election in her local Minas Gerais that she was expected to win on name recognition alone. Former Environmental Minister Marina Silva, who won over 21% of the vote in the 2014 elections, received just 1% of the 1st round vote, just shy over 1m votes. To the delight of most Brazilian voters, many of the mainstream politicians have been thoroughly rebuked.

As the world is beginning to notice via the #EleNao campaign and international election coverage, Bolsonaro is a well documented homophobe, misogynist, and racist, as well as a former military commander who expresses sympathy for the torture-laden military dictatorship regime that led Brazil for more than 20 years. In one of the world’s largest (and relatively young – just since 1988!) democracies, a man who is being likened to Trump (somewhat simplistically), and more recently to Hungarian President Viktor Orbán and Filipino President Rodrigo Duerte for his populist and authoritarian bent is just three weeks away from assuming the Presidency.

The always-fascinating Robert Muggah of the Instituto Igarapé, a Brazilian think-tank, wrote an op-ed piece in the NYTimes that I think is a useful summary of the uphill climb that Brazil must undergo over the next years, which will only be further complicated by Bolsonaro inevitable election. Trust in politicians, whether at the local, state, or national level, is as low as it’s ever been, which is part of Bolsonaro’s appeal. His solutions are extragovernmental, or overly simplistic so as to ignore the political process.

His challenger, the PT’s Fernando Haddad, winner of 29.3% of the vote, represents a party that was at the forefront of much of the graft and corruption that has made Brazil a source of national embarrassment, and continues to be maligned by much of the Brazilian populace.

The New Republic optimistically posted an article in the wake of the first round results, entitled The Man Standing Between Brazil and Authoritarianism. In the coming weeks, I believe we’ll see many such articles imploring Brazilian voters to unite around Haddad as the lesser of two evils. Unfortunately, I believe this article, and the hopeful opinions of many are too optimistic about Haddad’s chances. While I believe the economist and University Professor Haddad is much more of a centrist than he lets on (or at least hardly the radical communist his detractors paint him as), his party has chosen to tether him directly to the jailed Lula, rather than trying to offer any nuance to the Brazilian electorate. As lampooned in John Oliver report (and personally seen in campaign posters), the Workers’ Party has essentially created a situation where Haddad is a glorified Lula ‘stooge,’ as the Party has tried to capitalize on the jailed former President’s popularity rather than actually try and field a differentiated candidate.

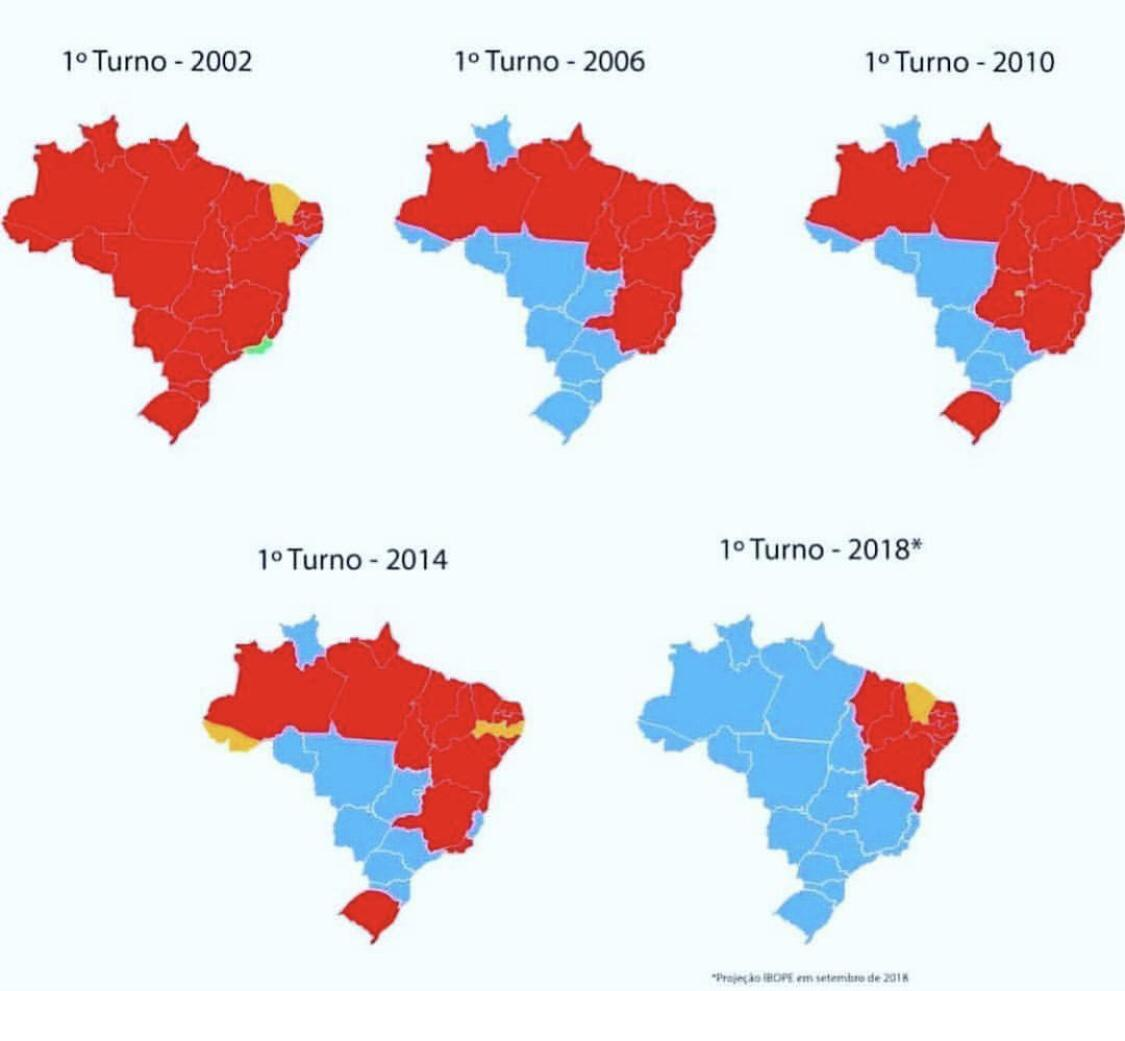

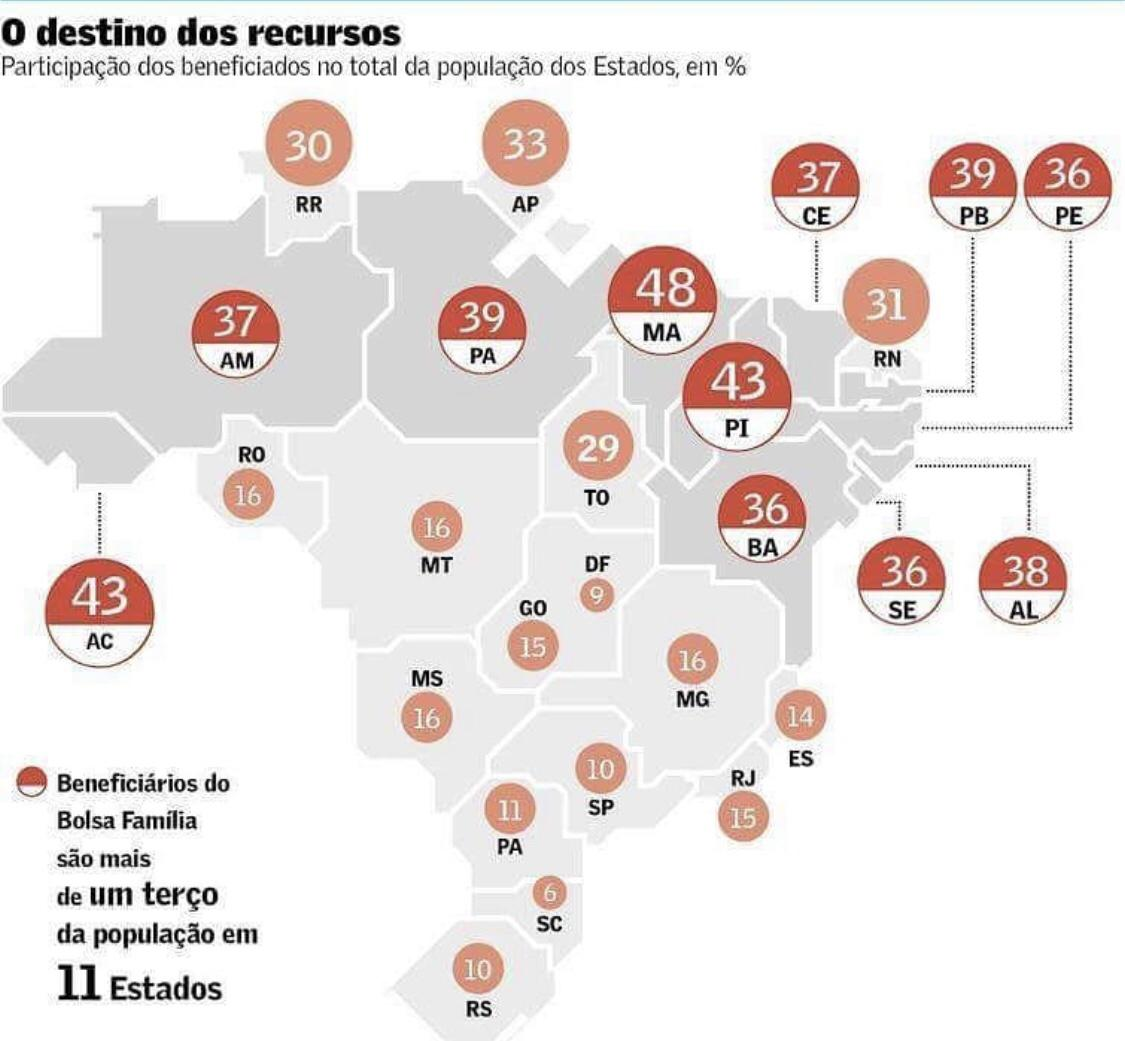

Two interesting graphs shared by economist and Linkedin commentator Ricardo Amorim contextualize the ubiquity between Haddad, Lula, and the Workers’ Party, and the PT’s decline in popularity, and continued stronghold on the Northeast region of Brazil. As many point out, Lula’s tenure saw millions of Brazilians brought out of poverty, both via macroeconomic headwinds and as recipients of Lula’s most famous government program that won plaudits around the world, the cash-for-school attendance Bolsa Familia.

Graph one: The States (in red) where the Workers’ Party won the majority in the First Round

Graph two: The % of the population (per State) who participate in the Bolsa Familia financial assistance program:

As seen by the lower proportions in the South and Southeast regions of Brazil, it is not hard to see how resentment has been stoked by the right-wing Bolsonaro against the PT and the North East, leading to further division and a stark choice between the right-wing Bolsonaro and leftist Haddad. Playing into this false dichotomy, the Brazilian real and stock exchange (up 5%) were strongly positive today, indicating a clear-preference for Bolsonaro’s simplistic calls for privatization and market friendly policies, and his temporary deputization of the economy to the Chicago-educated Paulo Guedes. For those in the US reading this – remember Gary Cohn?

In a country with tens of political parties, it is hardly surprising to see the second round results pit the anti-party Bolsonaro (with 50% disapproval ratings) against the entrenched Workers’ Party (with 50% disapproval ratings). Unfortunately, most centrist voters who voted for other candidates in the first round are likely to opt for Bolsonaro over the Workers’ Party. The socialist failure of Venezuela is at the forefront of the minds of many, and given the pandering / squandering of the Dilma Rousseff regime (Lula’s successor from the Workers’ Party), with its political corruption, redistribution of wealth, and mismanagement of government-run businesses.

As the Economist summarizes in an article alarmingly entitled Brazil is shaping up for a unique kind of financial crisis, the next President of Brazil will have to tame an ever-increasing government spending situation, including a bloated pension system that will only continue to grow (now at 55% of public spending). As the Magazine notes, an inability to adequately address the fiscal deficit and indebtedness in the 2020 Budget will spell near-collapse, and certain capital flight, a falling currency and rising bond yields.

This is the situation that the next Brazilian President will inherit. Outsider or not, we will soon see the result of the will of the Brazilian people, and its downstream impact. In typical lighthearted yet dour Brazilian fashion, all I can say is that it won’t be boring, and will continue to be educational.

One thought on “Brazilian Elections Update – The people’s will: a Face-off between 2 polarizing candidates”